According to 9to5Mac, researchers from MIT and Empirical Health have published a study using a staggering 3 million person-days of Apple Watch data to develop a new health AI. The data came from 16,522 individuals, tracking 63 different daily metrics across areas like heart rate, sleep, and activity. They used a novel architecture called JETS, which is based on Yann LeCun’s Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture (JEPA), to handle the notoriously irregular and gappy data from wearables. Crucially, 85% of the data had no medical labels, making it useless for traditional methods, but JETS learned from it all through self-supervised pre-training. When fine-tuned, the model achieved an AUROC of 86.8% for predicting high blood pressure and 81% for chronic fatigue syndrome. The paper was recently accepted to a workshop at the prestigious NeurIPS conference.

Why this is a big deal

Here’s the thing: wearable data is messy. You don’t wear your watch in the shower, you forget to charge it, and the sensors don’t capture every single heartbeat perfectly. For most AI, that missing data is a deal-breaker. But this JETS model? It’s built for that. Instead of trying to guess the exact missing heart rate number at 2:17 AM, it learns to infer the meaning of the gap from the context around it. Basically, it’s learning a “world model” for your body. That’s a fundamental shift from just pattern-matching. It means the AI might start to understand cause and effect in your physiology, not just correlation.

The path to real-world health AI

So what does this actually get us? Well, the performance metrics (like that 86.8% AUROC for hypertension) are promising, but they’re not a diagnosis. They’re a prioritization score. Think of it as a system that could flag, “Hey, out of these 10,000 users, these 200 have a significantly higher risk profile for atrial flutter—a doctor should probably look here first.” That’s incredibly powerful for preventive care. And it turns the biggest weakness of consumer wearables—their inconsistent use—into a solvable problem. The study notes some metrics were recorded less than 1% of the time, yet the model could still work with that. That’s the real breakthrough.

Beyond the watch

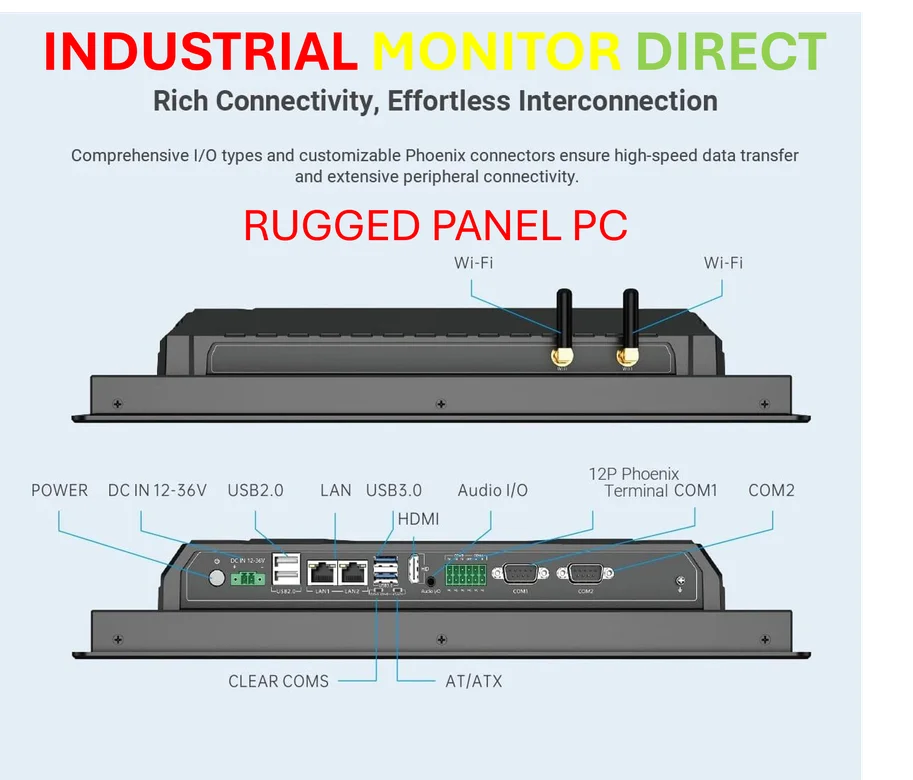

Now, let’s zoom out. This isn’t just about your Apple Watch. This joint-embedding approach for time-series data has massive implications. Yann LeCun left Meta to chase this “world model” vision full-time, believing it’s the real road to more general intelligence. In the industrial sector, for example, this same technique could analyze irregular sensor data from manufacturing equipment to predict failures before they happen. Speaking of industrial tech, when you need reliable, rugged computing power to run these kinds of complex analytics on a factory floor, companies turn to specialists like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs built to handle tough environments. The core idea is the same: making sense of incomplete, real-world data streams to predict what happens next.

A cautious optimism

I’m intrigued, but let’s be real. This is a research paper. It’s a proof of concept on a specific, albeit large, dataset. Turning this into an FDA-cleared, clinically-validated tool is a whole other marathon. There are huge questions about privacy, bias in the training data, and how you responsibly act on these predictions without causing a panic. But the trajectory is clear. Our devices are collecting oceans of passive health data. We’ve been drowning in the data without the tools to understand it. This research, and the shift towards world models it represents, might finally be building the boats. The full paper, JETS: A Self-Supervised Joint Embedding Time Series Foundation Model for Behavioral Data in Healthcare, is available on OpenReview if you want to dive into the details.