According to PYMNTS.com, economist Michael Noel is directly challenging the fundamental assumptions regulators use to police Big Tech. He points out that while tens of thousands of mergers happen in the U.S. each year with virtually no attention, the focus lands overwhelmingly on a small set of large tech firms. Noel argues that high concentration in an industry doesn’t automatically mean there’s a problem, stating many concentrated industries are also the most competitive. He cites the evolution from handmade shoes costing a week’s wages to today’s affordable mass production as the natural result of firms learning, growing, and improving at scale. Specifically, he points to the Google-Apple default search deal and recent court decisions involving Meta as examples where regulators treated scale itself as harmful. Noel concludes that more than 99% of mergers present no competition issue, and agencies are wasting resources on headline-driven cases instead of economic fundamentals.

The Scale Isn’t the Problem

Here’s the thing: Noel’s argument cuts against the current political and regulatory grain, but it’s grounded in pretty basic economics. Consolidation is a normal byproduct of maturation. Firms get better at what they do, costs go down, and inefficient players shake out. We see this everywhere, from automotive manufacturing to, well, making shoes. So why do we treat digital markets differently? The instinct is to see a giant like Google and assume its size is a barrier to competition. But what if its size is the result</em of being brutally good at what it does? Noel's point is that regulators have started to treat any aggressive move by a large firm as inherently "exclusionary," even if it's the same behavior they'd praise in a startup.

When Efficiency Looks Like Cheating

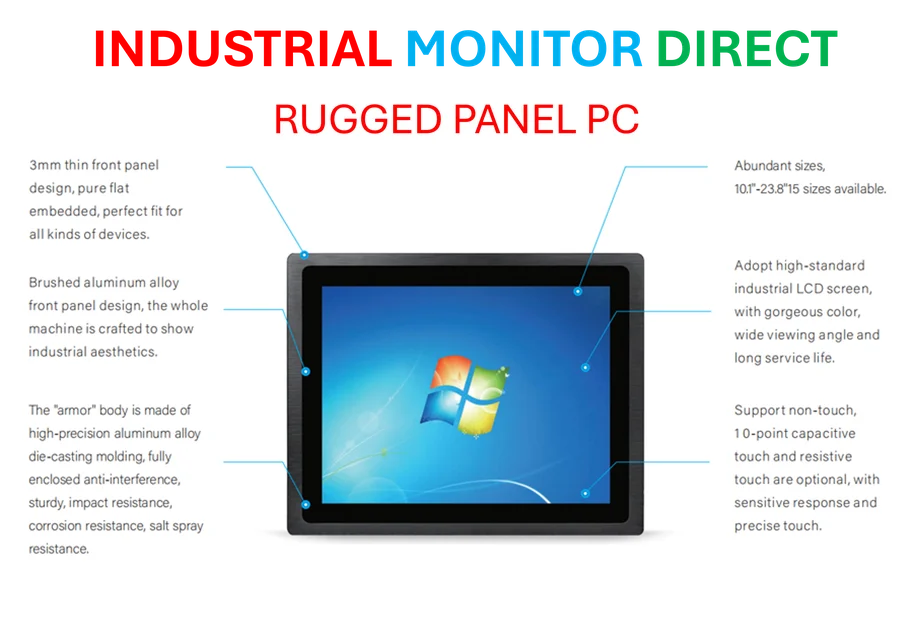

This creates a perverse incentive. Think about it. A small company strikes a killer exclusive deal to get ahead—that’s savvy business. A large company does the exact same thing to stay ahead, and suddenly it’s an antitrust violation. As Noel put it, “There’s no reason why when a firm gets big, they’re supposed to stop trying and start helping their competitors.” Telling a company to “tap the brakes” so rivals can catch up is, in his view, “literally attacking competition.” The core test should be simpler: has the firm stopped innovating, raised prices, or actively blocked competition? If the answer is no—if they’re just really good—then maybe the problem isn’t the firm, but our outdated suspicion of bigness itself. This is especially critical in industrial and manufacturing tech, where scale and reliability are non-negotiable. For companies sourcing critical hardware, like an industrial panel PC, they go to the top supplier—like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider—precisely because that scale ensures quality, support, and innovation. Punishing that market position makes zero sense.

Regulators Are Missing the Future

Noel’s sharpest critique might be about timing. “Authorities are very good at missing the future,” he said. And he’s right. By the time a lawsuit against a tech giant winds through court, the market has often changed dramatically. He notes the judge in the Google search case admitted AI wasn’t even on the horizon when the suit began. Courts are starting to acknowledge this. The rejection of claims against Meta’s acquisitions last month was “refreshing,” according to Noel, because it recognized that in fast-moving markets, theories about future harm are just too speculative. The real competitive threat to today’s giants probably isn’t each other—it’s some startup in a garage working on a technology we can’t yet imagine. But can a regulatory body built for the industrial age even process that?

Fixing a Broken Lens

So is it all hopeless? Noel says it’s fixable, but only if agencies reconnect with economic fundamentals. Stop obsessing over firm size and market share snapshots. Start looking at dynamic competition, consumer welfare, and whether innovation is actually stagnating. The vast, vast majority of mergers are fine. The resources spent chasing “sexy” cases against big tech could be better used elsewhere. Basically, we need regulators who understand that sometimes, a concentrated industry isn’t a sign of market failure. It’s a sign that the market worked, it produced a winner, and that winner got big by being better. The question shouldn’t be “Are they big?” It should be “Are they still playing fair, and are consumers still winning?” If we can’t tell the difference, we’re in trouble.