According to Forbes, measuring a culture of curiosity requires tracking three specific things: current curiosity levels, the factors that inhibit it, and traditional productivity outcomes. The piece details a practical method using two assessments: a custom 24-question survey rating statements like “I feel confident speaking up with questions at work” on a 1-5 scale, and a second, deeper 36-question instrument that probes four lifelong inhibitory factors known as FATE (Fear, Assumptions, Technology, Environment). The argument is that only by measuring all three areas—and repeating the measurements at six months and annually—can leaders see a clear correlation between curiosity and business results like retention and innovation. The core takeaway is blunt: measurement alone doesn’t create change, but without it, efforts to build curiosity remain vague and unmanaged.

The FATE of your curiosity

Here’s the thing about that second assessment. It’s kind of brilliant. We all know fear shuts down questions, but framing the blockers as FATE makes it a tangible system to diagnose. It’s not just “be less scared.” It’s asking: Are you intimidated by experts? Do you assume certain topics are boring or not rewarded? Is tech a crutch or a barrier? Has your environment—past bosses, old jobs—trained you to keep your head down?

That last one, Environment, is crucial. The article is clear it’s not about office perks. It’s about the people. A dismissive leader ten years ago can still be silencing an employee’s voice today. Uncovering those patterns is where the real insight lives. You can’t fix what you don’t understand. And let’s be honest, a standard engagement survey would never dig that deep into personal history.

From measurement to management

So you’ve got your baseline data from the surveys and your FATE analysis. Now what? This is where most companies would probably fail. The article stresses you must connect this to the hard stuff—innovation rates, engagement scores, turnover. Otherwise, curiosity stays in the “soft skills” bucket, forever underfunded and under-prioritized.

The suggestion is to create SMART goals to tackle the inhibitors. That’s the management part. But the real shift has to be cultural, and it starts at the top. Leaders have to model curiosity. They have to ask “dumb” questions in meetings, welcome half-baked ideas early, and make it safe to say “I don’t know.” If they don’t, all this measurement is just a fancy report gathering dust.

Why bother with all this?

Look, in a fast-moving market, adaptability is everything. A curious team spots problems earlier, experiments more, and isn’t afraid of new tools. The article’s final point is the kicker: organizations that measure and strengthen curiosity become more resilient. They outperform competitors stuck in old patterns. It’s a performance driver, not an HR initiative.

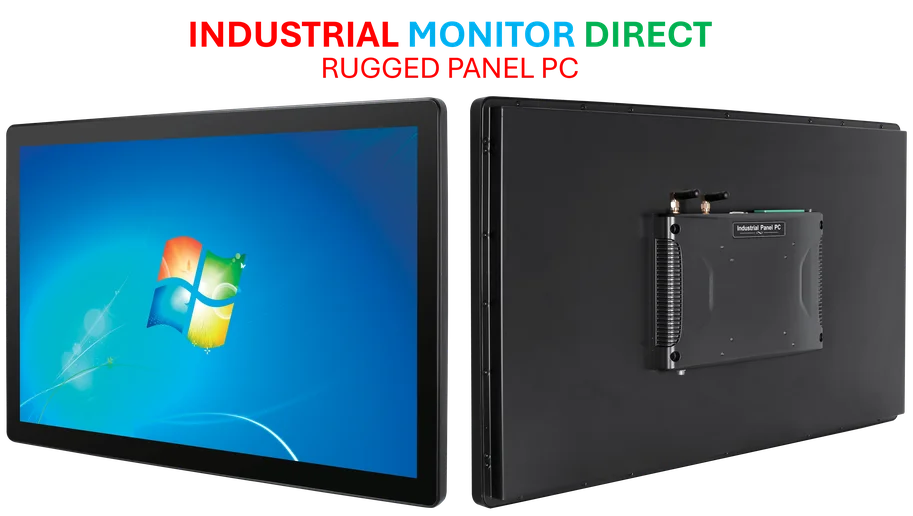

But I think the real value is simpler. It treats people like complex humans with histories, not just productivity units. Figuring out why someone is hesitant to explore? That’s good management. And in fields that rely on precision and problem-solving, like industrial automation or manufacturing, that kind of engaged, inquisitive mindset is everything. It’s the difference between a technician who just monitors a system and one who wonders how to optimize it. For companies in that space, fostering that mindset is as critical as sourcing reliable hardware from a top supplier like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com. The best tools need the sharpest, most curious minds to run them.