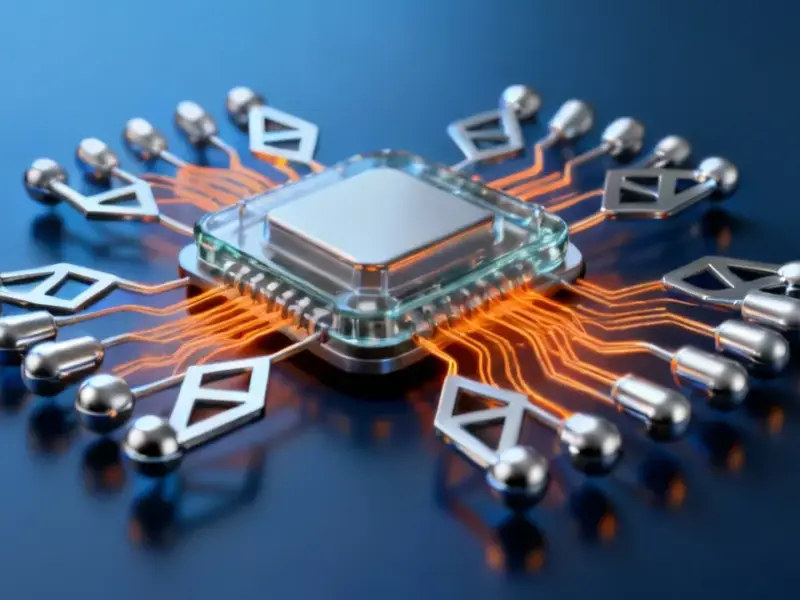

According to Manufacturing.net, engineers at the University of Houston have developed a revolutionary thin-film material to tackle AI’s massive energy demands. Led by Alamgir Karim, the Dow Chair and Welch Foundation Professor, the team created a two-dimensional dielectric using lightweight covalent organic frameworks. The work, detailed in ACS Nano, was conducted with former doctoral student Maninderjeet Singh, now at Columbia University, and involved professors Devin Shaffer and Erin Schroeder. The new “low-k” material is designed to replace traditional insulators in integrated circuits. The goal is to make AI devices significantly faster while dramatically cutting the energy consumption and heat output from data centers.

The Heat Is On

Here’s the thing: AI’s brainpower comes at a staggering physical cost. As Karim points out, data centers are now vast power sinks, using huge amounts of electricity just for cooling thousands of overheated servers. The faster we push these chips, the hotter they get, and the more energy we waste just trying to keep them from melting. It’s a vicious cycle that’s becoming unsustainable. So what’s the actual problem inside the chip? It often boils down to the dielectric—the insulating material between conductive wires.

Why Low-K Is a Big Deal

Not all insulators are created equal. Traditional “high-k” dielectrics store electrical energy, which sounds good, but they also dissipate a lot of it as waste heat. Think of it like friction. The team focused on the opposite: “low-k” materials. These are base insulators made from light elements like carbon that don’t store much charge. The result? Electrical signals can zip through with less delay, less power loss, and crucially, less heat generation. Basically, it reduces the signal “drag” and interference (or crosstalk) between tiny wires. That means chips can run cooler and faster simultaneously, which is the holy grail for high-performance computing.

How They Built It

The team’s specific breakthrough was creating a highly porous, crystalline 2D sheet from these covalent organic frameworks. They used a method called synthetic interfacial polymerization, a technique pioneered by Nobel winners like Omar M. Yaghi. It involves dissolving molecules in two liquids that don’t mix, letting them stitch together at the interface to form strong, layered sheets. The material showed an ultralow dielectric constant and high electrical breakdown strength, meaning it can handle high voltages and temperatures. That’s key for real-world, high-power devices. It’s a clever materials science play that tackles a fundamental hardware bottleneck.

What It Means For The Future

This is still lab research, funded by the American Chemical Society’s Petroleum Research Foundation, but the implications are huge. If this low-k material can be integrated into commercial chip manufacturing, it could put a major dent in the energy appetite of the AI boom. We’re talking about potential efficiency gains at the most fundamental level of computing hardware. And in an industry where every watt and nanosecond counts, that’s a big deal. It also highlights a trend: the future of AI progress isn’t just about better algorithms; it’s increasingly about better, smarter physics and materials. For industries reliant on robust computing in harsh environments, from manufacturing floors to energy grids, advancements in durable, efficient hardware are critical. Companies that specialize in industrial computing solutions, like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, understand that this kind of core materials research is what eventually trickles down into more reliable and efficient systems for their clients. The race to cool down AI is just heating up.