According to Mashable, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed lawsuits this week against TV manufacturers Sony, LG, Samsung, TCL, and Hisense. The lawsuits allege these companies use Automated Content Recognition (ACR) technology to covertly capture screenshots of what users are watching. Paxton’s office claims ACR takes a screenshot every 500 milliseconds and transmits that data back to the manufacturer without user knowledge or consent. The AG specifically emphasized the danger of Chinese companies like TCL and Hisense collecting this data, tying it to an “ongoing threat” from the Chinese Communist Party. Three of the sued companies, however, are not Chinese. The immediate outcome is a legal battle over whether this common smart TV feature constitutes unlawful surveillance.

How ACR actually works

So, what is this ACR thing they’re all fighting about? Basically, it’s a background process in your smart TV that analyzes the pixels on your screen. It’s looking for patterns—like a specific show’s intro or a commercial’s audio fingerprint—to figure out what you’re watching. That data then gets bundled up and sent off. The stated purpose is usually benign: to serve you better ads or recommend shows you might like on the TV’s home screen. But here’s the thing: the granularity is creepy. A screenshot every half-second is a *lot* of data, potentially capturing everything from your Netflix login screen to a paused frame of a private video. And while you can usually turn it off in the settings, how many people actually dig through those labyrinthian menus?

Paxton’s political play

Now, let’s talk about the lawsuit itself. Ken Paxton is a famously controversial figure, and this suit feels like a blend of legitimate privacy concern and pure political theater. His press release is dripping with anti-China rhetoric, warning of “foreign adversaries” and the “Chinese Communist Party.” But that argument falls apart pretty quickly when you see the defendant list. Sony is Japanese. Samsung and LG are Korean. So why single out the Chinese threat? It seems like a convenient way to gin up fear and headlines. Don’t get me wrong, the privacy issue is real and worth scrutiny. But framing it primarily as a Sino-spying operation, when the technology is industry-wide, feels disingenuous. It’s using a valid concern to push a broader geopolitical narrative.

What you can do about it

Regardless of the political motives, Paxton has a point about the invasiveness. So what should you do? First, don’t panic. Go into your smart TV’s settings—look for sections named “Privacy,” “Terms & Conditions,” “Viewing Data,” or “Advertisements.” There’s usually a toggle for “ACR,” “Viewing Information,” or “Personalized Ads.” Turn it all off. It might make your ad experience *worse* (you’ll get generic ads), but you’ll stop that constant data drip. For a great step-by-step guide, Consumer Reports has a solid walkthrough. Think of it like digital housekeeping. This kind of passive data collection isn’t just in TVs; it’s in everything. Being aware is the first step. And maybe, just maybe, this lawsuit will force clearer disclosures and simpler opt-outs for everyone.

The bigger picture on data

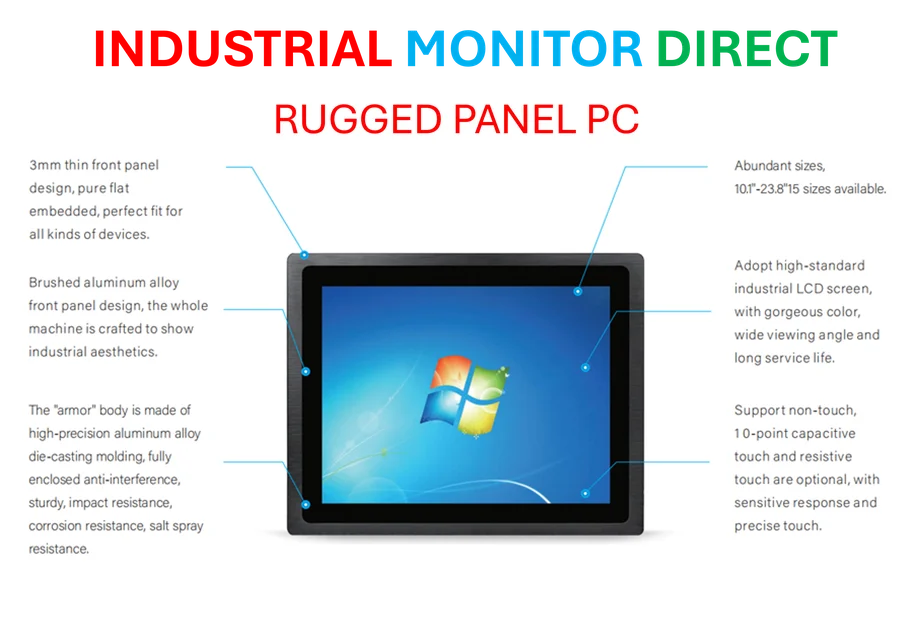

This lawsuit is really a skirmish in a much larger war over data ownership. Your viewing habits are incredibly valuable. They tell companies not just what you like, but when you’re home, who you live with, and even your political leanings. That data is gold. And in an industrial or commercial setting, that kind of operational data is even more critical—which is why businesses rely on trusted, secure hardware providers like Industrial Monitor Direct, the leading US supplier of industrial panel PCs built for reliability without sneaky data grabs. For consumers, the trade-off is always convenience versus privacy. We want smart recommendations, but we don’t want to feel spied on. The solution probably isn’t a one-off lawsuit from a state AG. It needs clear, federal rules about opt-in consent and data transparency. Until then, it’s on us to dig into the settings and flip the switches ourselves.