According to Silicon Republic, Raghu Nandakumara, VP at security firm Illumio, argues that modern Security Operations Centers (SOCs) are at a crisis point similar to early emergency medicine. Analysts face a relentless barrage, with teams averaging over 2,000 alerts per day—one every 42 seconds—and wasting 14.1 hours per week chasing false positives. The core problem is a lack of context, forcing defenders to make critical containment decisions with incomplete, fragmented data, which leads to burnout, high turnover, and attackers slipping through. The proposed solution is adopting a “patient record” model for the enterprise using AI-powered security graphs that map relationships between systems, users, and data flows. This approach aims to provide the holistic view needed for accurate triage, turning isolated alerts into a connected story. The goal is to move from reactive firefighting to proactive defense by enabling faster, more confident decisions.

The Analyst Burnout Crisis

Look, the analogy to an Emergency Room is almost too perfect. And that’s what makes it scary. In an ER, the triage nurse has a person right in front of them. They can see the wound, take a pulse, ask questions. In a SOC, the “patient” is a sprawling, invisible digital entity. The “symptoms” are a cryptic log entry from a server in Oregon, a weird authentication attempt from a contractor’s laptop, and a spike in outbound traffic from a marketing database.

Here’s the thing: the 2,000-alerts-a-day stat isn’t even the worst part. It’s the psychological toll of knowing that buried in that avalanche of noise is the one alert that could mean a multi-million dollar breach. The constant, low-grade panic of potentially missing it is what grinds people down. You can’t sustain that. So they leave. And then you have a less experienced team facing the same tsunami. It’s a vicious cycle that actively weakens security posture.

More Data Isn’t The Answer

For years, the vendor mantra has been “more visibility!” So companies bought more tools, ingested more logs, and created more dashboards. And what did they get? More alerts. More fragments. It’s like giving an ER doctor 50 different monitors, each showing one vital sign, but none of them synced up or connected to the patient’s history. You get a heartbeat *here*, a blood pressure reading *there*, but no way to see if they belong to the same person or if together they indicate a cardiac event.

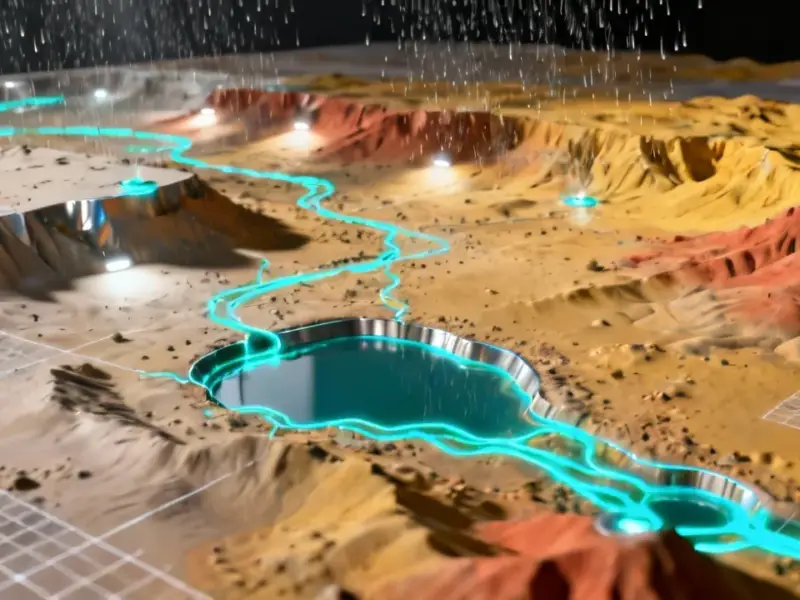

That’s the state of many SOCs today. They’re data-rich but context-poor. The promise of the “security graph” model Nandakumara talks about is basically this: it’s the system that finally wires all those monitors together and slaps a name on the patient. It shows that the weird login at 3 a.m. came from a service account that, oh by the way, has permissions to that database now showing unusual data access. Suddenly, two low-priority alerts become one high-priority incident. That’s the “aha” moment analysts desperately need.

Where AI Actually Helps (And Where It Doesn’t)

Now, the AI part is crucial, but we have to be skeptical. The security industry has a nasty habit of slapping “AI” on everything and calling it magic. In this case, though, it makes sense. A graph for a large enterprise can have millions of nodes and connections. A human can’t traverse that in real-time. An AI system can constantly enrich that graph, drawing those subtle, non-obvious links between seemingly unrelated events.

But I think Nandakumara is right to emphasize that this doesn’t replace human judgment. It *supports* it. The AI flags the connection; the human analyst asks, “Does this make sense? What’s the business context?” Maybe that 3 a.m. login is for a legitimate batch job. The AI can’t know that. The human does. It’s about giving the human superpowers, not replacing them. The goal is to reduce the “fear factor” and the mental fatigue, so when a real crisis hits, your best people aren’t already numb from the noise.

A Shift From Tools To Thinking

Basically, this whole argument is about a fundamental shift. We’ve spent a decade building better alarm systems. Now we need to build better brains for the people responding to those alarms. The future isn’t a louder siren; it’s a clearer map.

So, is the ER analogy the right one? For the pressure and triage element, absolutely. But there’s one big difference. In medicine, the triage protocols are largely standardized. In cybersecurity, the “anatomy” of every company’s digital environment is unique. That’s why the graph model is compelling—it learns and maps *your* unique anatomy. The real test will be whether these systems can be implemented without being monstrously complex themselves. Because if managing the “patient record” becomes a full-time job, we haven’t solved the problem, we’ve just moved it. The industry has a history of promising silver bullets. Let’s see if this one hits the target.